By Konstantin Slavin, MD, FAANS

Department Of Neurosurgery, University Of Illinois At Chicago

One of the most important elements in making the correct diagnosis in patients with facial pain is the precise determination of the pain’s location. Facial sensation comes from multiple nerves that overlap in their areas. However, some specific areas are primarily linked to specific nerves and branches. And just as the upper lip location of the trigger points suggest involvement of the maxillary nerve and the pain in the region of the root of the tongue and the tonsil – of the glossopharyngeal nerve, the pain that focuses inside the ear canal tends to point toward the intermediate nerve (nervus intermedius) that is the culprit of so called geniculate neuralgia, also known as the nervus intermedius neuralgia.

The nervus intermedius, sometimes called the 13th cranial nerve, is a very small structure that travels along the seventh (facial) and eighth (vestibulocochlear) nerves from the brainstem toward an opening in the petrous bone, the porus acousticus. The facial nerve is a predominantly motor nerve; its main function is the control of facial muscles on one side of the person’s face. As opposed to the motor portion of the trigeminal nerve that controls the muscles of mastication (chewing), the facial nerve is in charge of the muscles that move the face, close the eye, make person smile, etc.; when the nerve is damaged, the patient exhibits facial palsy (as in Bell’s palsy), and when it is irritated, one side of the face

twitches (hemifacial spasm).

The vestibulocochlear nerve carries information from the inner ear; the cochlear part is responsible for hearing (acoustic sensation) and the vestibular part is balance. Injury to the cochlear portion of the eighth nerve would produce loss of hearing / onesided deafness; its irritation may result in tinnitus (ringing in the ear). Vestibular nerve damage may not be very noticeable if only one side is involved, but the nerve irritation may cause vertigo and dizziness. All this information becomes relevant in the context of geniculate neuralgia as the surgery on the nervus intermedius involves dissection and manipulation of the seventh/eighth cranial nerve complex.

In some cases, the diagnosis of geniculate neuralgia is quite straight forward, especially if the shooting pain stays exclusively inside the ear canal. More often, however, the pain spreads to the earlobe and the areas around the ear, and then clinician has to decide if the pain location suggests involvement of other cranial nerves, including trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, vagus, etc., or if it stems from adjacent anatomical structures such as temporomandibular joint, the earlobe itself, middle ear contents, and so forth.

For this reason, the physical examination by a qualified specialist becomes important. Sometimes an evaluation by doctors of multiple backgrounds (otolaryngology, oral surgery, neurology) is needed to establish the correct diagnosis and rule out other possible pain sources, each of which would require different treatment. Interestingly, imaging tends to be normal in patients with geniculate neuralgia, although it is not uncommon to discover vascular contact or even compression of cranial nerves that may or may not be in any way connected to the pain’s origination.

In the past, the International Headache Society included well-defined criteria for geniculate neuralgia in its International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD). The current, 3rd edition of this classification [1] divides all cases of pain attributed to a lesion or disease of nervus intermedius into several categories, including the classical (caused by vascular compression), secondary (due to a tumor or multiple sclerosis) or idiopathic (no evidence of compression or other identifiable causes) types of nervus intermedius neuralgia. To qualify for geniculate neuralgia according to ICHD-3 classification, the patient should be experiencing “brief paroxysms (intermittent or sporadic) of pain felt deeply in the auditory canal, sometimes radiating to the parieto-occipital region (near the back of your head, where the top and back parts of your brain meet).”

The diagnostic criteria specifically describe recurring pain that occurs in paroxysmal attacks lasting from a few seconds to a few minutes. This pain is characterized by its severe intensity and can feel shooting, stabbing, or sharp. Additionally, there is usually a trigger zone located in the posterior wall of the auditory canal or the periauricular region (area around your outer ear).

The classification also distinguishes geniculate neuralgia from painful nervus intermedius neuropathy. Unlike the intermittent pain of neuralgia, this neuropathy involves continuous or near-continuous pain that is dull and felt deep within the ear.

This condition may arise in cases of herpes zoster, which can occur after a herpetic infection (known as post-herpetic nervus intermedius neuralgia), result from a tumor or injury, or appear without any identifiable cause.

When I talk to my suspected geniculate neuralgia patients about the pain location and try to explain involvement of the neighboring nerves, I frequently refer them to the excellent illustrations from our colleagues at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota [2] or Barrow Neurological Institute in Arizona [3] shown here in this article.

When it comes to the treatment of geniculate neuralgia, conventional wisdom dictates ruling out treatable causes and addressing them to eliminate the pain; this is particularly relevant for cases of secondary geniculate neuralgia. As with any other types of facial pain, the surgery for patients with geniculate neuralgia is reserved only for those who fail to improve with non-surgical modalities, including medications, interventional treatments (such as nerve blocks), alternative approaches (including acupuncture), etc. and are truly impacted by their pain in terms of quality of life and ability to function.

In the neurosurgical practice, most patients have already tried and failed most or all of the available treatments, and therefore our discussions usually focus on confirming the diagnosis, ruling out other conditions with similar presentations and differentiating neuralgia from neuropathy. After that, the patient may be offered surgical options and presented with descriptions of surgical details, risks and potential complications. This allows our patients to weigh all the pros and cons of surgical treatment and make an informed decision on whether to proceed with surgery as the next step.

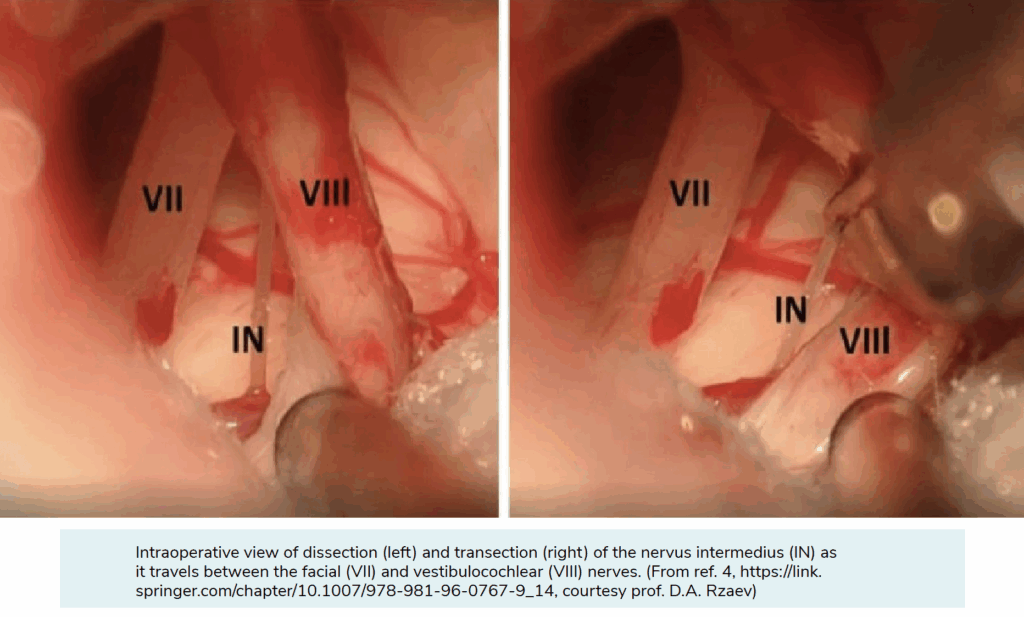

Needless to say, the surgeon’s preference is usually to avoid any kind of destruction and relieve the patient’s pain by simply eliminating the source of pain. However, even in those cases where vascular compression of the nervus intermedius may explain the pain, resolving the situation by microvascular decompression – as we do in most patients with trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm – may be quite challenging, for many reasons. This is why more often surgeons would consider cutting the nerve root (so called rhizotomy) to permanently cure the geniculate neuralgia. The procedure is done through a small skin incision behind the ear on the side of pain; it is done under general anesthesia with the help of a surgical microscope, special cranial nerve monitoring, and dedicated microsurgical instruments [4]. Most patients are kept in a hospital for a day or two after the surgery, and the sutures or staples are removed two weeks after the operation during the clinic visit.

Multiple surgical series reviewed the results of operative treatment of geniculate neuralgia. The consensus, based on decades of experience and many professional publications, is that most patients benefit from their surgeries. More than 90% of patients report either complete resolution or significant improvement of pain due to geniculate neuralgia after their surgery, and the results tend to be long lasting and consistent among many reporting centers all over the world. Interestingly, some patients who had successful treatment needed help with more than one nerve causing their pain. Because of how their pain was spread out, doctors had to treat multiple nerves at the same time during surgery — combining rhizotomy on the nervus intermedius, with related intervention on either the trigeminal nerve or the glossopharyngeal/vagus nerves.

Based on these excellent results, one may state that there is a definite hope for people who continue to manage the pain associated with geniculate neuralgia, and if the severe pain inside the ear canal becomes disabling and does not respond to conventional treatments, surgery is a consideration. The risks of surgery should not be downplayed or ignored, but the risk of complications should be weighed against the potential benefits of surgery, especially if it is done by an experienced surgical team that specializes in management of complex facial pain patients.

References:

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018 Jan; 38(1):1-211. (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/0333102417738202)

DeLange JM, Garza I, Robertson CE. Clinical reasoning: a 50-year-old woman with deep stabbing ear pain. Neurology. 2014 Oct 14; 83(16):e152-7. (https://www.neurology.org/doi/pdfdirect/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000893)

Robblee J. A pain in the ear: Two case reports of nervus intermedius neuralgia and narrative review. Headache. 2021 Mar; 61(3):414-421. (https://headachejournal.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/head.14066)

Dementevsky VS, Lekchnov EA, Rzaev DA, Slavin KV. Intermediate nerve neuralgia. In: Li ST, Zhong J, Sindou M, Sekula RF (eds.) Microvascular Decompression Surgery, 2nd ed. Springer, Singapore, 2025, pp. 12-135 (https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-0767-9_14)

Depiction of the sensory nerves shows the innervation of the ear and surrounding anatomy. Each box with its corresponding color illustrates each nerve’s distribution. Sensory distributions may overlap. Illustration by John Hagen, Mayo medical illustrator. (From ref. 2, https://www.neurology.org/doi/pdfdirect/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000893, courtesy of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research)

Neuroanatomy of the nervus intermedius, showing the nervus intermedius (red line) and the distribution of its sensory innervation (red shading), the facial nerve (purple line) and the distribution of its sensory innervation (purple shading), and the superior petrosal nerve (green line) and the distribution of its sensory innervation (green shading). CN, cranial nerve; EAC, external auditory canal; IAC, internal auditory canal; n, nerve; SN, solitary nucleus; SSN, superior salivatory nucleus. (From ref. 3 https://headachejournal.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/head.14066, courtesy of Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, Arizona)

Intraoperative view of dissection (left) and transection (right) of the nervus intermedius (IN) as it travels between the facial (VII) and vestibulocochlear (VIII) nerves. (From ref. 4, https://link.springer.com/ chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-0767-9_14, courtesy prof. D.A. Rzaev)